This story contains descriptions of PTSD symptoms and a description of a personal trigger

This is Part Two of a multi-part series on hypervigilance and catastrophic thinking. Click here to read Part One.

Last Sunday I got married. If you’ve been following me on instagram or getting my weekly emails this may not be news to you, but for everyone else, last week, in front of 12 of our family members, Charlie and I did the damn thing. Many have been congratulating us, just like I congratulate them when they get engaged or married; it’s what we are all trained to say. Social graces!

For me, I actually do feel like I deserve the congratulations. Not for getting married, (Hi Charlie! You’re my legal property now, baby!) because choosing to have the state recognize your union is not like, an accomplishment.

If I deserve congratulations it’s definitely for the work that I’ve done to manage my hypervigilance and catastrophic thinking. That work has been essential in order to feel hopeful enough about the future to want to get married. Getting married requires a tremendous amount of optimism (Hello 50% divorce rate! #romance) and optimism is tricky when your brain is hardwired to constantly prepare for the worst. For the past year, I’ve worked tirelessly in therapy to face the hypervigilance and catastrophic thinking (for more on what hypervigilance is, read my story about it here) that inhibited me from doing things I actually wanted to do, like getting to legally own Charlie.

How hypervigilance and catastrophic thinking cloud our vision of the future

A year ago, my therapist said something that rocked my damn world. I confessed to her that I was having distorted thoughts that I didn’t want to get married because, in my mind, if we never legally married that somehow when Charlie eventually dies it won’t hurt as much. I knew it was illogical; whether or not we formalized our relationship with the government wouldn’t change how devastating losing him would be. But sharing that deep-seeded fear unlocked something inside of me.

That’s when Sandy, my therapist, (Hi Sandy!) said something I will never forget. She told me that my inability to feel optimistic about my future was because, deep-down, I didn’t really understand that I actually had a future. Spending decades anticipating for the worst possible outcome in order to steal myself from future trauma had led me to believe that everything I loved would end tragically too soon, including my own life.

I desperately wanted a future, to have a powerful bombass career, to grow old with Charlie, to be a bubbie someday. It’s just that, at my core, I didn’t think that could happen for me because it was too good to ever be true. The story I had been subconsciously telling myself, and what my complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD) had been telling me, was that I must always be prepared for the most catastrophic outcome because it had happened so many times in my past.

Learning to confront the catastrophic thinking so we can let ourselves feel hopeful

I felt really sad coming to that realization, but more than anything I was so relieved to hear my therapist say that. Finally, I could understand why I’ve had such a difficult time making plans for the future and why I constantly feel terrified that time is passing too quickly.

In acknowledging that that’s what was happening inside of me, I began to work hard, with great intention. In each session, I would name all the ways I was bracing myself for the worse. My therapist would then have me close my eyes and imagine the different scenarios, whether it was about work or friends or my relationship with myself, and visualize the best possible outcome occurring in each of those situations.

In doing these visualizations, it’s not as though I became convinced the best would happen; like LOL, therapy isn’t actually magic. Rather, it was an intentional action I was taking to to rewire my brain into being open to positive outcomes in my life. If I spent 45 minutes once a week trying to imagine the best, then maybe, over time, I could train my brain to find some balance between my black and white thinking.

I didn’t even really notice that it had begun to work until I was in the middle of 16th Street walking home with Charlie last June and I proposed to him. I surprised myself. I hadn’t planned it, and I was shocked to see how happy I was; that I had the capacity to not automatically assume our lives together would end tragically, but rather, maybe we could die in each other’s arms old and in love Notebook-style. I was ready to be optimistic.

Managing C-PTSD and hypervigilance while getting married

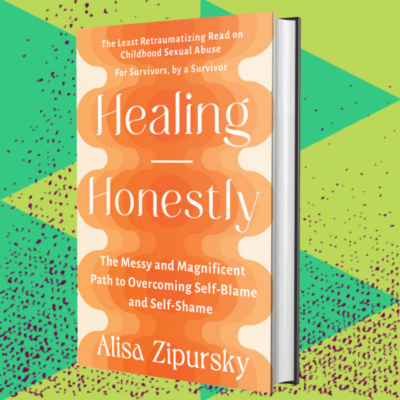

I wish I could say that I healed myself, that the experience was linear and pretty and wrapped up in a bow and shit. But this is Healing Honestly, and real talk, healing never looks like that.

The past three months leading up to getting married were some of the hardest I can remember (which we all know doesn’t necessarily mean much). I unrelatedly experienced one of the biggest triggers of my life. My biological father, the man who harmed me, was trying to get a hold of the people who love me the most to try to discredit me and isolate me from my support system. It was abusive and incredibly harmful for my health, and I felt my trauma return to me with the evil voices of shame, self-loathing and self-doubt creeping in.

With my C-PTSD on overdrive, the hypervigilance and catastrophic thinking took over, and for each positive feeling I had, I immediately thought of the worst possible thing happening.

Such as:

- I actually am really excited to wear my teal caftan wedding dress but what if my harm-doer triggers me the week before and I’m just in full PTSD trigger mode the entire wedding? I bet I won’t be able to enjoy any of this.

- I can’t wait to celebrate the marriage at this awesome historic tiki bar but what if I have to fake my joy in front of everyone because I’m triggered as hell but don’t want my trauma to ruin the wedding for everyone else.

It was completely natural that those voices of nihilism and pessimism would return when I was being re-traumatized and abused and I wish I could say there was some easy fix. I did the visualizations, I started boxing again, I upgraded my meds, I leaned heavily on my support network, but it took months to feel relief from the symptoms.

As I got closer and closer to the wedding I got increasingly nervous that I’d be triggered again. It helped to be honest with my people about that fear. My mom and I would talk each day and she’d ask me what are some things I can let go of that day in order to be kinder to myself and more protective of my own energy. I cancelled meetings, I relied on delivery services for things, I stopped ingesting the news, I put an out of office on my emails.

It did help to tell everyone around me what was going on so that they could help recognize those voices and provide me with comfort. You all know that laughing at my trauma is really essential for my healing, and so sharing some of my most outlandish catastrophic thoughts and being able to laugh about them was also very important for me. I could feel how nervous Charlie and my family were about my mental health leading up to the wedding, and it simultaneously made me more nervous (like I’d somehow let them down if I was traumatized during it) and also deeply comforted, loved and protected.

Everything went better than I truly ever let myself imagine, and by that, I was able to be present and feel tremendous joy in the moment. I was able to quiet the traumatized voices to feel my full self. I laughed hard, really really hard; I smiled really big and I meant it; I danced and it felt euphoric. I had moments of dissociation, but I knew that was just my coping mechanisms coming into play to just try to give extra protection from potential trauma and I tried my best to accept that and then let go. Most of all, for the first time in months I didn’t see my life in black and white; I could see in the full spectrum of color, and that felt really really good.

I know that there will be more triggers in my future. Doing this work guarantees it, as does, you know, just being a human with C-PTSD. I know I’ll hear my voices of doom and pessimism; they’re a part of me that stem from a time when I needed them to help keep me safe. But it feels so good to know that there are moments, whole days, hell even an entire week, when I get to hear the hopefulness inside myself and feel totally free to let it shine.