This story contains a discussion of child sexual abuse, and the effects of trauma, and talks about how many people who harm others are, themselves, survivors

Note: This piece is long, and you don’t need to read it all. If it feels like too much, just scroll to the bottom to read Tarana Burke’s tweets, and call it a day.

I’ve been avoiding writing this blog piece since I launched the site two years ago. To celebrate the two-year anniversary, I am going to honor something I learned since launching it: the hardest things for me to write are often the most worthwhile. The time has come for me to face my own anxieties and talk about survivors as abusers and what that means for accountability and ending sexual abuse.

It feels particularly relevant because of the headlines around Asia Argento, who, it was revealed, made $380,000 in payments to actor Jimmy Bennett after allegedly sexually assaulting him in 2013. Asia Argento is an actress who accused Harvey Weinstein of sexually assaulting her and became a prominent highly visible spokesperson of the #metoo movement. To be clear, I believe Jimmy Bennett when he says Asia Argento sexually assaulted him when he was 17 years old. I also believe Asia Argento when she says Harvey Weinstein sexually assaulted her. The public conversations around Argento and Bennett made me realize I can no longer put off this conversation within myself, or all of you.

Before diving in, I want to acknowledge all those who have come before me and are also currently doing the critical work to talk about the weaponization of victimhood and intergenerational trauma. I also want to specifically shoutout to Amita Swadhin of Mirror Memoirs who has been public about the fact that her father, who sexually abused her, was himself a victim of child sexual abuse, and is leading difficult conversations about how we end the epidemic of child sexual abuse in the context of the legacy of colonialism and institutionalized racism. Another special shoutout to Tarana Burke the founder and leader of the #metoo movement whose tweets you will see later in this piece (if you read only one thing, let it be her tweets).

Why is it so hard to talk about abusers as victims?

As I mentioned, it’s hard for me to write about this, for a few reasons. First, for those of us who are familiar with the statistics of just how many abusers are victims, it can be hard for us to not feel like sometimes we are fated to hurt others. I always have great trepidation sharing statistics on this site because I never want a survivor to feel like they are destined to have a certain kind of life, such as any sort of negative health outcomes or mental health challenges but also that they’re destined to be an abuser themselves.

When I was first coming to terms with my own history of childhood sexual abuse I found that I was very very afraid to be around children. I feared touching them in any way. It wasn’t until I spoke with another survivor that I realized that I was feeling like I was contaminated. I felt like I had an illness living inside of me that was contagious and I was going to pass it onto the children I was near. (If you yourself have been feeling that way, I have found openly acknowledging those fears has been very healing for me. Additionally if you have access to a therapist, I recommend communicating with one about those fears, it definitely helped me). Talking about how abusers are often victims taps into my own past anxieties that I might harm a child the way I myself was harmed.

Abusers can weaponize their victimhood

The second reason this is so difficult for me to write about is because my abuser conditioned me to see him as a victim at the expense of my own humanity. Since I was old enough to remember, he systematically groomed me to believe that the world was against him and that I should feel sorry for him and take care of him, even as a small child. He is a clinical narcissist, and each time I tried to advocate for myself and my safety he would cry and ask me why I didn’t love him more. He used his victimhood as a weapon to keep me under his control.

Throughout my life, when I would think about breaking free of him, the one thing that would keep me in my abusive relationship was the fact that I felt sorry for my father. I was unable to see him as a perpetrator and hold him accountable because he conditioned me so effectively to see him as a victim.

In order to break through of my paralyzing feelings of guilt, I had to re-train myself to stop thinking of my father as a victim. If I thought about his victimhood, how he probably had a really terrible childhood and was “just doing his best”, I would be unable to leave. To this day, all these years later, I still struggle to accept the possibility of my father as both a victim and a perpetrator, even though I know there is a good chance that that is his truth.

Survivors are not fated to be abusers

What is important is that while a significant number of abusers are victims, the vast majority of victims do not become abusers. [If you want stats, please feel free to google, but again, not going to post them here for the aforementioned reasons]. We are not fated to harm others, but it also is our responsibility to ensure we don’t.

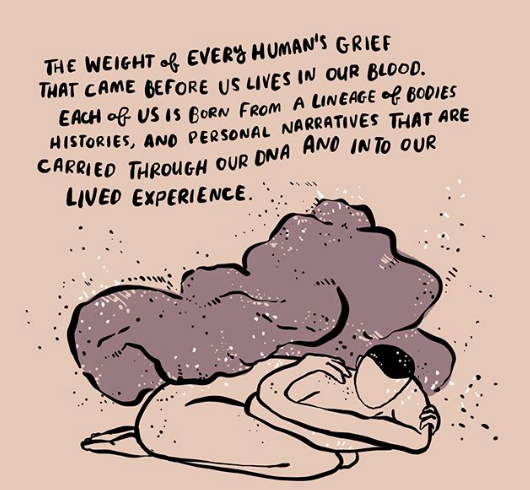

We can make decisions in our healing to take responsibility for ourselves and our actions. Abusing another person is not something that just accidently happens. Abuse is about power. While someone may have held power over us and misused that power to harm us, we also have power in other relationships in our lives, whether it is as bosses, parents, partners, etc. But we can also abuse this power in a larger cultural way, whether it is our privileged gender, race and sexual identity. For example, white women’s victimhood has been used as a tool of white supremacy to oppress black men since the dawn of time in America. It is our responsibility to both recognize and understand the power we can hold in our different identities and relationships so that we never misuse that power or harness it to harm another person. I think the beautiful art and words from the incredible duo of Caitlin Metz and Victoria Emanuela at On Being In Your Body says it best (all pics credit On Being In Your Body):

Why we need to acknowledge that survivors can be abusers

As much as I’ve wanted to avoid the subject I realize I’m doing no one, including myself, any favors by ignoring the fact that survivors can be abusers. Where I am in my own healing is that it’s easier for me to cope with a false binary: either my father is the sad pathetic man who was a victim of the world and didn’t know better and can’t be held responsible for his actions, or he is a monster. These past years, I’ve worked so hard to see him only as a monster, because I’m so afraid of seeing him as a sad pathetic man again and falling into the trap of feeling guilty for leaving him.

But this binary isn’t real and isn’t very helpful. The truth is both can be be true: My father both is a sad pathetic man who probably experienced some fucked up shit in his childhood and is possibly a victim himself, and also he needs to be held accountable and responsible for what he did to me.

Challenging the survivor vs. abuser binary

I need to face this false binary in my own life in order to be able to answer the questions people have been asking about whether Jimmy Bennett coming forward about his truth invalidates Asia Argento’s accusations against Harvey Weinstein. Again, we are presented with either A. Asia Argento is a victim or B. she is an abuser. But I believe her when she speaks about Harvey Weinstein sexually abuse her. And I believe Jimmy Bennett when he says she sexually abused him when he was 17 and she 37. All these things can be true at once, because we can both be abused by someone misusing their power and we ourselves can abuse our own power and harm another person.

“We have this binary because our mainstream solutions to violence have been put within the cirminal justice system, where someone is a victim and the other the perpetrator. The problem is that criminal justice is our main, and only, solution to violence,” says Kate Vander Tuig, sexual violence expert and best friend extraordinarie. Our justice system is set up to treat someone as either a criminal or a human being, and there are many corporations through the prison-industrial-system that make enormous profits telling the world that we must deny the humanity of people who commit crimes.

As a part of this binary, we see abusers as monsters, not as people. Yes, the actions that abusers take can be monstrous, but there are humans behind those actions, not creatures of the night.

Even though it is so challenging for me to acknowledge my father’s humanity, I’ve learned from leaders like Amita Swadhin that doing so is the only way I can begin to think about how we stop the epidemic of child sex abuse. Until we acknowledge that abusers are human beings who are misusing their power, we cannot really address how to stop abuse from happening.

In an effort to move away from this unhelpful binary, there are leaders within the movement, including some who advocate for transformative or restorative justice, who have talked about moving away from terms like “abuser”, and are instead using people first language such as “Someone who harmed and hurt you”. In my commitment to further exploring these ideas and challenging myself, I will be exploring using people-first language in future posts.

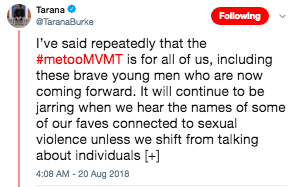

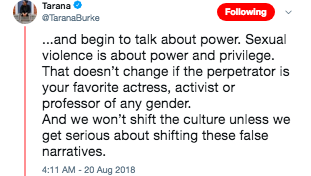

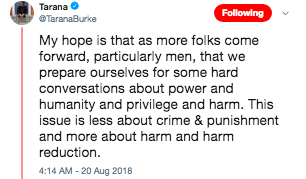

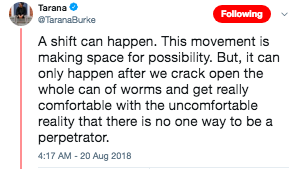

I want to conclude with the most important words in this piece, which are those of Tarana Burke, founder and leader of the #metoo movement whose leadership we should all be looking towards: